Placenta accreta: One of the lucky ones

This is my first post in two and a half years. As most writer-parents can relate, life marches forward, and certain projects and responsibilities (often the most pressing ones, your kids) claim your attention, while others fall off.

That being said, much has happened for me since last penning a Write Parent post in February 2023—the most significant of those events being the birth of my son in May 2024, over five and a half years after I had my daughter via C-section.

My son’s birth was a C-section, too. That high-risk pregnancy and involved delivery is what I write about today, after reading an illuminating and urgent article published yesterday in the NY Times, titled “A Grave Condition Caused by C-Sections Is on the Rise.”

It took about two and a half years to conceive our son. Compared to other people’s experiences, that’s nothing: there are couples who spend a decade or more trying to build their families.

Still, for us, two and a half years felt like a long time. In those years, I had a miscarriage, saw a fertility specialist, and underwent a hysteroscopy to remove uterine scar tissue that occurred after my first C-section—and that was preventing me from conceiving. Then, we kept trying.

In September 2023, when I learned I was pregnant, I was cautiously optimistic, afraid I would experience a second pregnancy loss. When I started bleeding one evening around the 8-week mark, I was sure I was miscarrying again. I phoned the on-call doctor, and she said to wait out the bleeding until the morning. If there was none when I woke up, everything was likely okay; if I was still bleeding, she said, come into the office.

Falling asleep that night was challenging, but I eventually succumbed. When I woke the next morning, I checked my underwear first thing. There was no blood. I felt weightless, giddy with relief. I whispered to my little one, a bundle of cells the size of a blueberry, “Thank you for hanging on.”

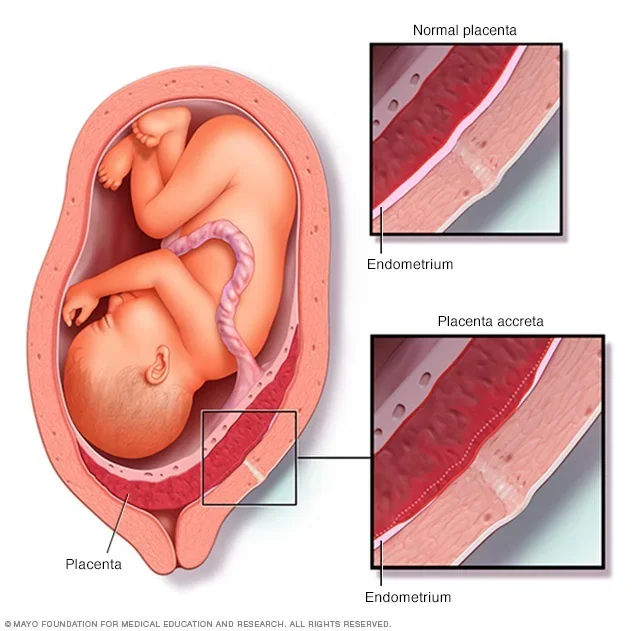

At a routine appointment around 12 weeks, I learned that I had placenta previa, a condition where the placenta covers the cervix. This could have explained the bleeding at 8 weeks, my doctor said. I was told not to worry too much yet—placenta previa often goes away on its own as the placenta shifts in the uterus. That did happen to me, in fact, but a few weeks later my doctor noticed something else going on in my uterus, something he suspected might be placenta accreta, a term I had never heard of.

Placenta accreta spectrum is a condition where the placenta attaches too deeply into the uterine wall. It can happen in several places along the placenta-uterine border, or even in just one spot. A placenta accreta diagnosis is serious and in most cases means a pregnant woman will deliver via planned C-section under the supervision of a large team of experts—as was my case. The delivery is planned several weeks early to prevent spontaneous labor and delivery, which can increase the risk of a severe hemorrhage and maternal morbidity.

When my doctor mentioned his suspicion of placenta accreta, one of my first questions was whether he thought I would have to deliver via C-section. After my daughter’s birth, I experienced complications and a severe infection post C-section, which ultimately led to uterine scarring that likely caused my subsequent miscarriage. I was really hoping to avoid a C-section this time around, I told him. He shook his head and said that if it turned out I did have placenta accreta, the most important thing would be to ensure the baby and I were healthy—which would almost certainly mean a planned C-section.

I was referred to a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist at NY-Presbyterian Columbia University Irving Medical Center in Washington Heights. The doctors there confirmed I had placenta accreta, and I immediately became a high-risk patient. My care was transferred to the MFM team, and I started taking Metro-North into the city each week from the Hudson Valley, where I live.

Traveling to doctor appointments while juggling work, artistic projects, and a child at home wasn’t easy, but I knew I was lucky: not only did I have healthcare—something none of us in this country can take for granted—I had an expert team that had identified my dangerous condition and was prepared to do everything they could to deliver my baby safely.

As I carried my son in my belly for the next 20 weeks, the numbers and possible outcomes weighed heavily on my mind: There was a 50% chance I would hemorrhage to such an extent that I would need a hysterectomy on the spot. If I did have a successful delivery, it was likely that my pre-term baby would need to stay in the NICU. Placenta accreta comes with a 7% maternal morbidity rate, and if I went into spontaneous labor before my C-section date, I was more likely to be included in that grim statistic.

In the days leading up to my delivery, I spent a lot of time with my 5-year-old daughter. We read books, cuddled up on the couch. I smelled the top of her head and willed my olfactory cells to remember that sweet scent forever, no matter what happened. I wrote her a letter before I left for the hospital, reminding her that I loved her more than the expanding universe.

The mothers mentioned in yesterday’s NY Times article probably hugged their older children goodbye, too. Tragically, unlike me, they never got to come home to their babies—not the older ones waiting for their return, or the new ones who never got to see their mother’s smiling face.

My son was born at 36 weeks. He weighed just 5 pounds, but his lungs were fully developed, and he never even visited the NICU. I hemorrhaged, but my excellent team of doctors was able to contain my bleeding and avoid a hysterectomy. My recovery was long and challenging, but I held my baby to my chest within hours of his delivery. I kissed his perfect forehead and nose, I nursed him, I watched his little chest rising and falling as he slept. His father and I took him home on his third day of life, and at our front door we met his big sister, who, gazing at him with wonder, whispered, “It’s you.”

My son, minutes after his delivery by the wonderful team at NY-Presbyterian Columbia in NYC

As reported by the NY Times, in the 1970s, 1 in 4,000 pregnancies was impacted by placenta accreta. Today, it’s 1 in 272. (Likely, this sharp increase is in part due to the proliferation of C-sections, which can cause uterine scarring that researchers suspect leads to placenta accreta.) The medical bills that follow these high-risk, complex deliveries are substantial, and those medical bills come in the mail whether or not the delivery is successful.

The United States of America owes its mothers and families—who build the nation minute by minute, decade after decade—affordable healthcare, funding for high-quality medical research that improves maternal and fetal outcomes, and support networks that provide care for families suffering under a system structured to work only for the luckiest.

Please share this NY Times article with your friends and family, spread the word about placenta accreta, and hold our representatives accountable to building a healthcare system that helps families come home to each other and grow together.